We thought we were damn good when

we started out. People hated our guts."

|

your emotional spectrum gets a little more involved," Mould

says, "a little wider, and it's not just screaming about how messed up the

government is and how you hate

your parents any more. It's..." "Playing

to a better medley," Joan says, cold-cocking him into stunned silence

with the malapropism. Finally, she asks the teen-mag question of which

is the calming influence, which is the wild one, and Bob cops to the

former, Greg admits to being in between, and Grant rolls his eyes. "We'll

be back with the eighty-five-year-old marathon winner and actor David

McCallum, okay?" Joan concludes. Okay, Joan.

A week later, Hüsker Dü is in Denver. All is not swell in the

Mile-High City: A lack of advance sales has caused the promoter to move

the gig from a beautifully restored downtown theater to Norman's Place,

way the hell out in the suburb of Aurora. In fact, it looks like he's

been keeping it a complete secret. The band goes to an in-store appearance

at Wax Trax, a funky, comfortable record store in a collegiate-looking

area. It looks like there are only six non-band, non-employee types in the

whole store. Over the next hour, several more people drift in, but most

don't recognize the band or know what they're doing behind the counter.

The guys are taking it instride, though, chatting affably with the fans,

signing album covers, posters and 12x12s, and surprising me with their

encyclopedic knowledge of America's underground bands. Of course, they've

played on bills with many of them. Bob Mould scores a stack of fanzines

to read.

"So how many songs have you guys released, anyway?" a fan asks, and Mould

jots some figures down in a long string, going back to the top to pull out

subtotals and comes up with an answer. One hundred thirty. More or less.

"How many unreleased?" "Not many. We tend to use what we record right away.

Maybe two or three songs. Hundreds on cassettes and in notebooks though."

"Hey," the fan says, looking at the sheet of numbers. "I recognize

that: card-counting." Mould's eyes light up. "Did you do any playing

when you guys played Vegas?" And they're off into a conversation about that.

It gets to be 4:30, and with soundcheck not until six, the question of

finding something to eat looms large. The issue of food is complicated:

Bob and Grant are strictly teetotaling vegetarians, a hard regime to hold

to on the road. We wind up at a Greek Mexican place and head off to the gig

via the hotel.

Greg Norton, as navigator, knows where everything is everywhere in America.

He has maps, for one thing, but he also has a hell of a lot in his head.

I guess after six years of cross-country travel that's not too surprising.

Tonight's gig is in a shopping center, close by a Gold's Gym and a

Fuddrucker's. Norman's Place is a teen club serving no alcohol, and even at

this early hour the parking-lot is swarming with rent-a-cops. In the dressing

room we find music writer Gil Asakawa with an older man he introduces as

George Beck, owner of the toy company that made Hüsker Dü. Gil

has talked Beck into coming along to meet the band and give them a new

copy of the game. Beck is friendly enough, although the sound coming through

the closed door is frighteningly loud for him. "Where the Child Can Outwit

the Adult!" it says on the Hüsker Dü box. According to New

Times, the game has a scandal in its history: An overzealous ad agency

inserted the subliminal message "GET

|

IT!" in a Canadian Hüsker Dü

TV ad, and Beck and his company were denounced in Parliament.

The band is really happy to see Beck and they trade Hüsker Dü lore

for a while. "Hüsker Dü is a Norwegian television show similar to

Lawrence Welk, too, you know, and when we played Norway the government asked

us to stop using the name," Mould reveals. So did you? "Naw." Then the

four of them settle down for a game which, considering Mould's methodical

mind, I'm surprised that Greg Norton wins.

The show begins early, and although the sound leaves a bit to be desired,

there is fire coming off the stage tonight. Playing for a small but

devoted group of fans, suburban punk-by-numbers kids and curiosity-seekers,

they let it rip. I wonder if the regulars here realize what kind of show

they're getting tonight, how seeing the light at the end of the tour-tunnel

is making the band cut loose.

I also think about how difficult this band seemed for me at first. Metal

Circus was a roar from one end to the other, but with a little bit of

melodicism peeking out to let me know this wasn't your average hardcore

band. Subsequent albums made that clearer until the magnificent single

"Makes No Sense At All" proved that this band could write hit songs, or at

least songs that were hits with me. But there has always bee an angularity

to Hüsker Dü— particularly Mould's numbers, which seem to

have very irregular meters (but only seem to) and emotionally opaque lyrics

that make surrendering to the music just a little more work than it is with

most bands. The hooks only sink in after three or four listenings. After

that, the floodgates open and I remember how I had the same trouble with

the early Who. True, Grant's not the flashy drummer Keith Moon was, but

Greg's bass fills in more rhythmically than Entwistle's. The Mould/Townshend

comparison works (and I'm not talking about their noses, either), except

that Bob doesn't leap around. Where the Hüskers have it over the Who is

that they have two prolific songwriters and a third who's getting back into it.

When I ask Grant about the differences between his songs and Bob's, he says,

"The fact that we're two different people might have something to do with it.

I mean, Bob and I aren't each half of Paul Westerberg."

"We started in the same place," Bob elaborates, "and developed differently,

separated quite a bit, and I think now are getting more the same."

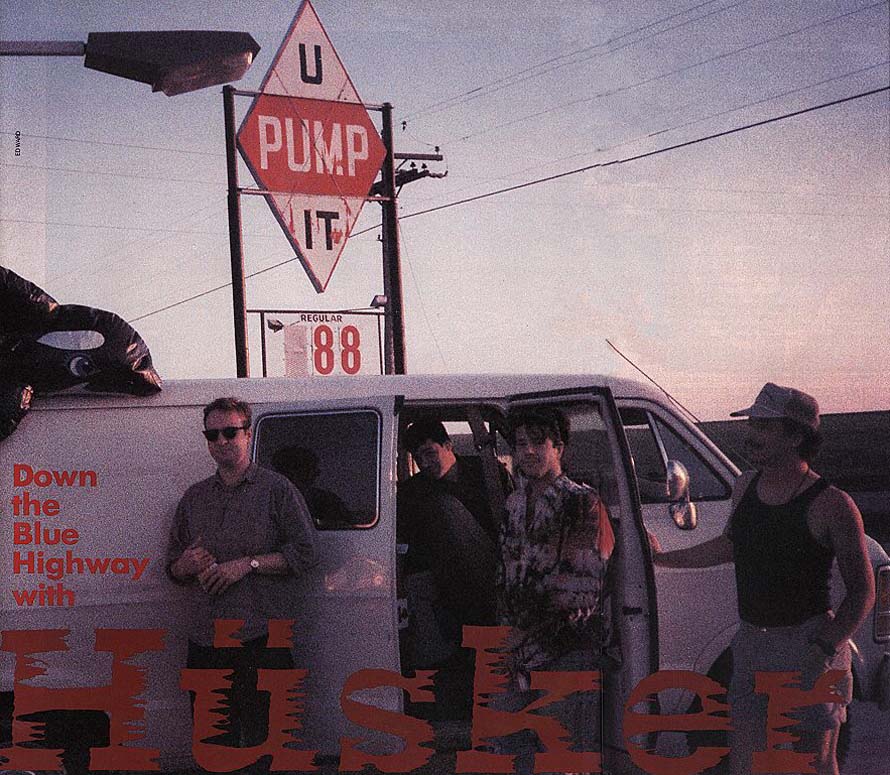

The next morning we prepare to leave for Kansas City. Warners publicist Les

Schwartz has rented a car and the band have a van. Yeah, van; no Silver Eagle

tour bus for these guys.

The tour is almost over: Only Kansas City and a gig the next night in Decorah,

Iowa remain. It hasn't been an easy one so far. The band had been off the

road for a while and was enjoying it after virtually living in the van for

five years. It was hard getting back, if even for six weeks. Two weeks

before the tour was to start, their manager, David Savoy, killed himself,

plunging the band's affairs into Bob Mould's competent but overworked hands

for the first time since Savoy had taken over in August '85. The band elected

to hold off finding new management until after the tour, so Bob's toting an

extra briefcase and making more phone calls every day.

|

Playing to a better medley? "I don't know. Money hasn't changed the way we

do it."

|

|

|

Since the band doesn't have to play until tomorrow night,

they're going to take their time. First stop is Federal Express, where

Bob has some stuff to mail off to the Today show, which is going to

broadcast a week from the Twin Cities and wants Hüsker Dü as guests.

After that, it's decided we'll find something to eat, and I get an idea of

Greg's road-sense. We drive along the interstate until an exit with several

franchises appears. Greg exits and bypasses the pancake houses and burger

joints for several blocks until we find Hai's Vietnamese Restaurant.

Ta-dah! Good food that even veg-heads can eat, even if the vegetarian aspect

of the menu isn't immediately obvious ("Oh no!" Bob exclaims after a quick

perusal, "They kill everything here!"). The food is wonderful, but the big

hit at Hai's is the rich espresso dripped into a glass and poured over ice.

Considering that it's almost three and the drive east has yet to begin, this

goes over very well with Greg, who also has a couple of Cokes.

Grant, Greg and soundman Lou Giordano head off to the K-Mart to buy

electrical supplies to rewire part of the van's interior. Bob and I head

to an Oriental market, where even more kinds of coffee are gleefully

purchased. We emerge to find the rest of the guys fussing around the

van, discovering they're not going to be able to do the work on the

spot because the dashboard padding has to be removed. Grant has found a

huge inflatable killer whale which he's trying to blow up. Greg, getting

wired from the multiple caffeine hits, gives us directions, and at four,

we're off.

Grant, Greg and Lou get the van. Bob and I climb into Les' rental car. Bob's

been mentioning that if we get to Kansas in time, he might visit "Bill," who

lives in Lawrence. "Is this some friend of yours?" I ask.

|

"Bill Burroughs,"

Bob explains. "We've known him for a while. Actually, Naked Lunch

was my huge revelation in college. I'm originally from Malone, New York,

which is way upstate. My parents own a, literally, mom-and-pop store. I

mean, you have to walk between the refrigerator and the stove to serve the

customers. Anyway, I got this complete scholarship to Macalester College

in St. Paul, I guess because they had need of a few smart poor kids, and I

had this boring job where I could read a lot. One night I got ahold of a

copy of Naked Lunch and read it all at one sitting. I was pretty

green then, and I guess it showed me some stuff."

"College is where we got the band together. I met Grant one day when I was

going to the grocery store. There was this guy wearing a leather jacket,

crankin' the Ramones through this PA in the middle of Grand Avenue, this

proper middle-class neighborhood. We found we had similar taste in music—

we were buying a lot of the American independent stuff, a lot of the British

stuff that was coming out in '77 and '78. We were just kidding one day and

he said, 'Do you play an instrument?' I said, 'Yeah, I play guitar,' and

Grant said, 'Oh, I play drums.' So we called each other's bluff and it

turned out we could play."

Bob was working in a record store called Cheapo Records whose owner had another

store where Greg worked (and where Grant had been pestering the management

for a job for some time). Eventually the three hooked up, playing "a lot

of wild noise" in Greg's basement.

"We had our own theory on how to change the world," Bob continues, and I

guess one way was— you have to bear in mind that we were all seventeen,

eighteen years old when this

|

"We're Hüsker Dü, not Bob Mould or

Grant Hart and two unlisted sidemen."

|

was going on— through our common interest in music. We ended up writing

what we thought were real catchy songs, but they were real abrasive and real

fast. Faster than bands had ever thought of playing before. In hindsight,

you can go back and look at some of the early stuff the Beatles did and you

can see how fast they played when all the yid was drink and take speed. Not

that we patterned ourselves after the early Beatles, but.... Were influenced

by a lot of things. I was listening to a lot of punk rock and a lot of, not

so much free jazz, but weird fringe music. Grant came from much more of a

pop background, and Greg was from a more jazzy end. We just did what we did.

It was pretty natural. We didn't sit down and have a world domination plan.

We thought we were awfully damn good when we started out. People hated our

guts."

Careful Bob, they kill everything here.

|

The early Hüsker Dü not only played an unpopular kind of music—

although the Twin Cities was a more receptive place for punk than many—

but they were from St. Paul, which enjoys the same sort of "second city" status

that Brooklyn does to Manhattan, or Oakland to San Francisco: Nothing cool

can come from a place like that. So they took what gigs they could get.

"We've done our share of 3.2 bars (pouring low-alcohol beer for eighteen-

to twenty-one-year-olds) and old folks' honky-tonk polka clubs and other

wacky gigs," Mould recalls, "but we did demo tapes before we played out,

4-track stuff that we thought was the greatest stuff in the world. After

we'd been together a year, a year and a half, we decided to put out a single.

We did three songs at Blackberry Way with Steve Fjelstad in August 1980.

We had people documenting live shows for us even back then, and we took

'Statues,' which was a studio song, and 'Amusement,' a live track, got a loan,

and put that out as a single. We pressed up 2500 of them, printed the sleeves

ourselves, stuffed them all into plastic bags and sat there and looked at them

for a couple of months.

"In March of '81 we decided to go down to Chicago, just for the hell of it,

to level the entire

|

city. We met the SST people there at one of the hell gigs,

the one with the

blue paint. Oh, that gig.... We got psychotic one night when we played

this club, bouncing off the walls, picking up hammers between songs and

smashing everything in sight. There were two lights in the whole place and

we had them focused on the mike stands so all people could see was these

silhouettes and these bright lights staring them in the face. And at the end

of the set, we just went nuts. There were no dressing rooms, just a storage

closet behind the stage, and one of us went back there and found this big

thing of blue latex paint. I was out of my fuckin' mind, so I just picked

it up and pitched it over the drum kit and it landed on the floor. The top

flew off and blue paint went all over the place. This girl, who was the

club-owner's roommate, dressed head to toe in leather, decided she was going

to scoop up the paint with what was left of Grant's cymbals and pour it

over his drum kit. She had a cymbal-full of blue paint, and just as she

got to the kit, Grant came out, picked her up, power-slammed her into the blue

paint so she was covered, her whole backside, and people decided they were

going to pick her up by her elbows and bounce her off the walls, leaving these

blue buttprints all around the club. Needless to say, we didn't get paid,

although I think we sold some records. This was before what I consider

hardcore was even hardcore. We pretty much...it was the Who."

Well, now. Imagine that.

In May, as soon as school let out, the band rented a van andspent the next

three and a half months on the West Coast, where "we did a lot of gigs for

twelve bucks, twenty bucks. If we could play a gig for twenty bucks and

have a place to stay, we'd do that. A lot of generic beer, a lot of

sandwiches, a lot of days without eating. But we discovered that, lo and

behold, there were other bands doing somewhat the same thing we were doing."

And the rest, as they say, is discography; first Land Speed Record

came out on New Aliance, then the first SST record, the Metal Circus EP.

Suddenly the trio from (ugh) St. Paul was one of America's leading

avant-garde bands. From there, they set up the cycle of tour, record, tour,

record, tour some more and record some more, that they only broke with the

six-month hiatus that led up to Warehouses: Songs And Stories.

Even— or maybe especially—America's leading avant-garde bands stand

a good chance of turning into crispy critters if they don't watch it.

You leave the hills behind in Colorado. It's amazing how you can start the

day with snow-capped peaks looming overhead and within a matter of a couple

of hours the whole countryside flattens out and becomes, well, Kansas. The

aggravation of the road is taking its toll on the homesick Hüskers.

When we cross into the Central time zone they let out a big sigh of

relief— almost home. Bob quotes his lyric from "Celebrated Summer":

Somewhere in April time they add another hour."

|

"The underground community is more

a series of tunnels than a hole."

|

After we gas up, Bob takes Grant's place in the van and Grant jumps in with

Les and me. I take over the wheel and point the car east. The van overtakes

us and stays just barely visible ahead on the plains. Van driver Greg is

in a hurry.

Now in direct contrast with card-counting Bob Mould and straightforward,

mechanically-inclined Greg Norton, Grantzberg Vernon Hart (sorry, man, I had

to tell 'em) is not the most, shall we say, linear member of Hüsker

Dü. It can be maddening, the way he never finishes sentences, his

mind having rushed on to something else, leaving you to...But you can usually

get his.... On the other hand, he tends to be very epigrammatic.

He talks about playing the couch circuit in the band's early days and I say

the sort of underground community that supported so many bands was

wonderful. Says Grant: "The underground is more a series of tunnels than a

hole." After four hours of rigorous conversation with Bob, Grant's

playfulness and general good humor give me the clue to the other side of the

band's appeal. At a Hüsker Dü gig in Austin, a Dutch fan approached

me and asked, "Zo, are you a Bob Mould fan or a Grant Hart fan?" and then I

spent the intervening weeks developing a theory that one was a more hard-rock

writer and the other more of the pop guy. Grant dismisses it with a short,

"That's a bunch of bullshit." (About half of the pop stuff I like is by

Mould, and the other half by Hart.) On the other hand, he freely admits

that the songs he writes on keys are differently structured from those he

writes on guitar.

But it's also clear that this end of the tour has left Grant pretty

exhausted, so mostly we just trade general observations or drive along

having conversations like this:

Grant: "I've never been in the same mood twice."

Ed: "That's an interesting thought. You really think that?"

G: "Yeah."

E: (stalling, trying to figure that one out) "That's good.i You're

very lucky."

G: "I've probably got six or seven categories of moods."

E: (increasingly puzzled) "But you don't slide into them the same way

or experience them the same way?"

G: "I'm sure."

Or Grant Hart tells a joke: "There was this guy who woke up one day and all

he heard was drums. Everywhere he went, drums pounding, pounding in his head.

And the doctor listened to his story and said, 'You got here just in time.'

So the doctor pulls out a needle and gives the guy a shot, and the drums

disappear. Then the bass solo starts..."

We've lost the sun, and even though the moon's not up yet we can still see

the horizon as we drive along. Reconnoitering at a rest-stop, we notice that

we're not quite halfway across Kansas, and it's decided that the next stop will

be someplace to eat. Grilled cheese again. Convinced that the van will

catch up with us, we leave without talking to Bob and Greg.

That turns out to be a big mistake. We set out with Grant at the wheel,

revved up and doing around ninety. Suddenly the van comes up behind us, and

Greg, mad that we left without him,

|

passes us and disappears down the road.

So much for our navigator.

About three hours later we approach Kansas City

and realize that although we're headed to another Holiday Inn, we have no

idea where it is. Over the next two hours, the vision of the Holiday Inn we

passed on our way into the city dances in my head. We should have stopped

there just to use their computer to find out which one we were staying at

and get directions. But we didn't.

To keep from falling asleep, we've turned on the radio, which at 3:30 on a

Friday morning in Kansas City, isn't much. But a song comes onthe oldies

station: "Aquarius" by the 5th Dimension. "Awright!" Grant yells, and

turns it all the way up. He starts pounding everything in sight, driving

faster and faster. "I leaned to play drums to this song. My brother, who

played drums and gave me my first set, said it'd be a good one to practice to;

it had a couple of different beats in it.

Finally we find the suburb we're supposed to be in. There's a Holiday Inn.

We're ecstatic. It's the wrong Holiday Inn. We're pre-psychotic. The

place we're supposed to be is two freeway exits back. All the way there, Grant

is trying to figure out whether it would be more sadistic to leave a 6:30

or a 7:30 wakeup call for Greg Norton.

The next day starts late. The hotel is a Holidome, with most of the rooms

arranged around an indoor pool. Mould has decided there won't be time to

visit William Burroughs. Instead he takes the modem out and starts doing

business in his room. Grant takes the inflatable whale he bought in Denver

and decides to donate it to the swimmers inthe pool. He gets up to the

second floor and throws it in, to the delight of a bunch of kids. Throughout

the day he checks in to see who's on the whale, and at one point there's a guy

who must be seventy, all alone, riding it up and down the pool. Not much

of a motel-vandalism story. Like I said, he's no Keith Moon.

At four, the band shows up in my room. I ask why they still drive

themselves around. "Well," Greg, who does most of the driving, says,

"you like to drive." True enough, and there have been times when

I've pushed myself to do a lot of it on a day, but I don't think a six-week

tour.... "Driving ourselves on the road is something we've always done,"

he says. I guess it would be nice to have somebody that that's all they do, is drive." "It's aprt of our way of being independent from the situation as

well," Bob adds. "You're not tied to the equipment, not tied to the crew,

not tied to the interstate. Like yesterday, we can trail off and do something

for an hour, or goof off in the afternoon. Other bands have to be on the bus

at a certain time or else fly to the next gig and pay out of your wallet to

do it. We're real hands-on as far as the booking and routing of our tours is

concerned. This is the schedule we've picked."

Then there's the queston of the lyrics. in the interviews I've read, the band

downplays their importance, which is fine with me because I rarely listen

to lyrics. But if they're not important, why are they there? "To have a

title!" Grant states the obvious. "The lyrics are real important," Bob says.

"But it's like, the two ground-breaking bands of the 80s people constantly

refer to are us and R.E.M., and we've both got this problem. There are so many

levels you can take this band on. You can say, 'They're a great live band,

but I don't like their

|

|

records much' or 'I like their records but they're noisy live,' and the

lyrics are just a portion of it. People tend to focus on them as being some

kind of biblical...godsend or something. 'Here come some more words of

wisdom from God.' Those are just our thoughts, and what people want to

take them as is up to them. We're in a band that people like and look up to,

but you don't have to take this as the way you have to live your life. It's

like, this is what we are. You can take a look at it and make what you

like out of it. But don't do what we do just because of what we are. That's

what I mean by not taking it too seriously: They're serious, thought-provoking

lyrics, but to us." "It's what you're thinking about when you're

playing," adds Grant.

How about having three songwriters in the group, does that make it harder to

put an album together? "Not really," says Greg. "It's because we're

Hüsker Dü, not Grant Hart and two unlisted sidemen or Bob Mould

and two unlisted sidemen. There are a lot of songs the three of us have

written that aren't suited to the group." "When you get ready to make a

record, you have to look at what everybody has," Bob amplifies. "One thing

that was nice about this record was just the amount of jamming we were doing to

find out what the common vocabulary of the instruments was. And from that you

can whittle down what songs are going to work and which are better just left

in the notebooks. Now there were real separate styles on Candy Apple

Grey; it was real fragmented. It was so damned depressing, bleak.

Candy Apple Grey was the result of four-and-a-half years of not

stoping to take a look. We were due for a real bleak album and that was

it." "Yeah," adds Grant, "we get all these dark-circled faces coming up

saying, 'I really liked that album.'"

|

That's another nice thing about Hüsker Dü: They're accessible to

their fans, be they dark-circled or apple-cheeked. "It's hard to share with

somebody," Grant says, aware that he's framing another epigram, "if you

don't let them at the table." "We don't think of ourselves as famous," Bob

adds, " and so we don't have any right to do that. By being very public

with people, I expect them not to be very private with me. We're accessible

at one level and untouchable at another."

But the fame is growing. What about the possibility that you may find

yourselves with a hit on your hands? "I think every song we wrote is a

hit," Bob says, dead serious. "Maybe not compared to Bon Jovi, but I think

we write a lot better songs than ninety-nine percent of the bands that are

going right now. To be honest, there are a couple of songs on each album

that we pay extra attention to, some songs that are just begging to sound

a certain way. Like on Flip Your Wig, 'Makes No Sense At All' and

'Green Eyes' were the two songs we spent a lot of time on, to make sure they

were impeccable by our standards." And they have finally reached the point

where their songs are getting covered: To my utter surprise, the band says

that Robert Palmer encores with a version of ZZ Top's "Legs" that segues

into that masterpiece of controlled chaos "New Day Rising." I'd like to

hear that, although I guess I'm not prepared to sit through an entire Robert

Palmer show to do so.

"I don't know," Bob muses as soundcheck draws near. "Money hasn't changed the

way we do it. We stuck through the lean years and went through the things that

kill other bands." Does it get easier as you go along? "No. Your time

changes. You're a little more pressed. You spend more time answering mail or

administering the business end of it. We had

our own label for a while, Reflex, and

|

|

had a lot of bands we worked with

and helped out financially. We don't have time to do that anymore, and it

would hurt the other bands to pretend that we could so instead we'll produce

their records or give them information about booking tours and stuff. We're

all pretty busy outside the band. Outside the band? I mean the couple of

hours each day when it's not the band. Hey, we didn't get together

to get rich and famous. Now we're"— "obscure and middle-class," Grant

interjects— "self-supporting and well-known," Bob picks up. "I guess one

thing I'm proud of is that we've never bounced a check and don't owe anybody

any money. That's a lot more than most people get out of life."

"And while doing that," Grant sums up, "we've maintained a great relationship

with our art."

Which is just what they manage to do that night at the Uptown Theatre, a

giddily rococo joint that has seen the cream of Kansas City jazz, from Andy

Kirk to Jay McShann to Charlie Parker, under its roof. The older,

drinking-age crowd is downstairs, while the youngsters fill the balcony, and

this leads to a very weird incident at the show's end. Everybody's pooped

so the post-gig socializing is held to a minimum, although fans are

accommodated. Grant and I are walking around as the room empties, and I see

that the T-shirts are only twelve dollars. "I'm going to get one of those,"

I say, but Grant dissuades me, saying he'll get me one. "You sure? I can

buy one," I say. As we stand there. I fail to notice the mob that's held

back by the security. For some reason the kiddies have to be kept upstairs

for a while (until the liquor is put away?), and as Grant and I turn to go

back inside the hall, somebody yells, "Okay!" and the mob swarms down the

stairs, catching us up in the flood of bodies. They're lining up to buy

T-shirts, while almost

trampling one of the guys in the band that has,

|

presumably, excited them into this consumer frenzy. What, I wonder, is

their relationship to this art? What does Hüsker Dü mean

to them, other than an excuse to wear their Discharge T-shirts and goop up

their hair. Makes no sense at all.

|

Bob Mould:

"I have a number of mid-70s Ibanez Flying Vs; actually

the Rocket Roll Flying V is what it's called. I use GHS Boomer

Extra-Light strings and Jim Dunlop light picks. I also use a

Washburn acoustic electric, and I've got a Yamaha 12-string

acoustic. As for amps, Yamaha G-100 heads running 4x12s, a

Marshall and a Sonic, both with Celestion speakers, and I slave

those into Fender Concerts with stock JBLs. For effects I have a

Distortion Plus and a Roland SDE-1000 digital delay. That's just

live. The studio is, uh, other things."

Greg Norton: "I play an Ibanez Roadstar Series II RB 940 bass

guitar with a full-scale three-octave neck, and use GHS Boomer

medium-gauge strings. I've got a Peavey Megabass digital bass

head which is used with the Urei L-2 (DLA 48) and those both go

into an SVT cabinet that's got eight 10s in it and a custom-

built Batson cabinet that's got two 15s."

Grant Hart: "I have Joe Calato Regal Tip 7A sticks, a variety of

Chinese and Turkish cymbals, Yamaha cymbal stands, a Ludwig

Speed King foot pedal, a 7x14 solid rock maple bentwood snare,

a 9x13 rack-mounted tom, using a Galou rim and a 16x16 floor tom,

and a 24x14 bass drum, and a Yamaha throne and that's about it."

Epilogue: This is important to the guys: It's pronounced

Hoosker Doo. Or, as Grant says, "This isn't a band of husks."

|

|

|