working with punk producer Spot. "He comes from a different school of production," Mould

explained. "The sounds he hears in his head are unique, but not very fitting

to what we're doing now. A producer's job is to be critical of the

performance and the arrangements, and to have an idea of how the album should

flow from start to finish. I think I have a better grasp of that than Spot or

anyone else. Why hire someone who costs a lot of money to come in, sit around,

drink and point his finger? I can do that myself."

Apparently, Warners agreed. Major labels often pressure new bands into hiring

big-name producers to provide an accessible sound and to lend an objective

ear to the recording. "That's (the disadvantages in not using a producer) the

price we have to pay for having these other good qualities," Mould responded.

"Our albums, for better or for worse, aren't two hit singles and filler.

|

and the way they sound on record."

The main change during the recording was in the mood of the material. "The

tone of some songs got a lot heavier," he stated. "At one point, it sounded

real wimpy and saccharine. It was ridiculous! So I started looking at the

songs to discover what they were really about. I realized that one song

didn't need high background vocals, and another needed static stuck in the

corner of the mix, or a low-frequency tone. Subliminal things like that can

make it more aggressive. There's a balance between overblowing everything

and keeping it somewhat close to a live setting."

However, Mould was quick to point out that not all the material had to be

suitable for live performance. "It's Jekyll and Hyde," he remarked. We'll

never take the keyboard stuff out live," he stated. "I shouldn't say never,

but if we did we wouldn't have a fourth person on keys. We tried to

|

programmer would do after dropping the

needle on "Crystal" and hearing the abrasive guitar thrash practically shred

the speakers.

"To tell you the truth, I'm not worried whether they like it or not," Mould

retorted. "It's up to the band to be like the record and be happy with its

content. We like scaring the hell out of people; I like that noise at the

beginning. If it doesn't fit in a particular radio format, too bad. We

didn't make the record for radio; we made it for people to listen to. There's

a formula for pulling singles — the first release is usually song three

from side one, followed by song one from side two, then the title track, etc.

We didn't sit down and go through the hysterics of that. Our records are

musical progressions, from start to finish, through a number of emotional

changes."

Although several tunes could fit right into any AOR playlist, it wasn't because

of pressure by Warners to "mainstream" the sound. "I can't speak for Grant,

but I write songs I want to hear," Mould asserted. "I thought that was

what people liked about our band. The label's job is to find the qualities

in us they feel are saleable, and do that without selling us out. Sure, I

could see us on Top 40 someday, but we're not going to change anything to

accomplish that. Making Top 40 would probably make me write even harsher

songs. I jsut don't put a lot of stock in 'instant hit' songwriting. I don't

think there's ever much soul in it; it's a lot of formula. Writing a song for

Top 40 is easy; writing a song for yourself is difficult."

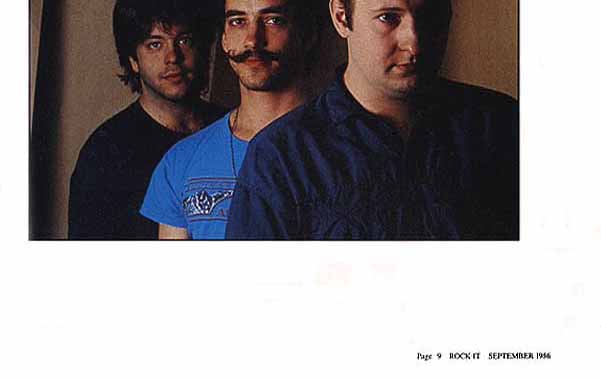

Already, Mould, Hart and bassist Greg Norton are setting their sights on the

next album. After almost a month of inactivity, Mould has been inspired to

write 20 new songs. "The amount of writing I do is in direct correlation to

the amount of living I do," he declared. "If you don't live, you don't

write. If you don't see anytihng, you have nothing to write about. Get out

of your back yard and do things, talk to other people and have some

experiences. When I start writing I start seeing lots of things, some things

I don't like, some things I do. Either way, it's a stimulus. Directly

proportionate to how much you take in is how much you put out."

In that light, there doesn't have to be an inherent conflict between Husker Du

and Warner Bros. Not when Bob Mould and company care far more about the

quality of their work than about the quantity of records they sell, and when

Warner Bros. respects them for that. "I don't have any commercial or career

goals," Mould concluded. "I just try to write a better song each time out.

Sometimes I do, sometimes I don't. But that's the thing I strive for —

to become a better storyteller, to write better songs and become a better

player." |

They're like diaries. Sometimes they're real nice; sometimes they're not so

nice. That goes for content as well as execution. Bands who hire big-name

producers still have clunkers on their records. I think our clunker ratio is a

lot lower than theirs."

Candy Apple Grey was recorded in Nicollet Studio in Minneapolis, where

the trio cut most of their last work and Mould produced other local acts like

Soul Asylum and Impaler. "It's real comfortable," he noted. "It's no more

than 10 blocks from where I live. In New York or L.A., I'd have to go back

to a motel after a session. Besides, I've done so much stuff there, over the

past two years, that I've got it pretty well wired for sound. I know all the

nuances of the room, be it the hertz problem or where the floor should be

filled with a little more sand, or certain bass taps that aren't quite right.

Little things like that you can't trust to an outside producer."

To say the Huskers engage in pre-production would be a gross understatement.

Not only do they know exactly what songs to record, but they practically know

the exact order of the songs before they start recording. "We still leave a

lot to chance as far as our sound goes, but we do know what songs work well

and in what order," Mould explained. "We tend to play songs in batches live

like they are on record, because we think they should be presented that way.

There's always last-minute changes, but they're nothing radical.

On Candy Apple Grey, there's really not much difference between the

first rehearsal of the songs

|

come up with a straight version of 'No Promise Have I Made,' but it wouldn't

work. A song like 'Whatever,' off Zen Arcade, has never been played

live. A lot of good ones haven't."

Other songs, like "Crystal," lend themselves to live improvisation. "I want to

do more of that in the future," Mould said. "'Crystal' has a pretty straight

arrangement, but there's lots of room to get outside. The same goes for 'Wit

And The Wisdom' and some of our instrumentals. Writing is such a loose term

when we're doing songs like that. It's not so much writing as it's pure

emotional expression."

|

ost of the songs on Candy Apple Grey fell into place, both in the

studio and on record. The major exception, "Crystal," became the disc's

inaugural cut practically by a process of elimination. "There was no other

place |

for it on the record," Mould admitted. "It's not a very good song to

end the album, and it'd stick out in the middle of side one. It became obvious

that we should set the pace for the album, so everyone would know wjere this

record was at. It wasn't a happy-go-lucky pop album."

That logic flies inthe face of "conventional" wisdom. Any promo rep will tell

you that almost all radio program directors, when evaluating a new act's

record, automatically play the first cut on the

first side. If they don't like

it, they probably won't even listen to the rest of the disc, and it won't

get airplay. Imagine what an unsuspecting

|